Nutrition affects more than just the cow’s digestive system. The effects of an imbalanced diet can be seen throughout the animal’s body. Of particular interest are concentrates, such as grain-based feed ingredients, that typically contain high amounts of sugar and starch.

When fermented by rumen microbes, sugar, and starch create an acidic rumen environment. Acids in the rumen can damage the gastrointestinal lining and creating localized or systemic inflammation, which can travel outside of the rumen.

Diet changes and lower rumen pH can also cause a shift in rumen microbial populations, which may favor species such as Treponema, which plays a role in digital dermatitis. By carefully formulating the diet and monitoring cow health, we can limit the occurrence of hoof health issues caused by nutritional imbalance and mismanagement.

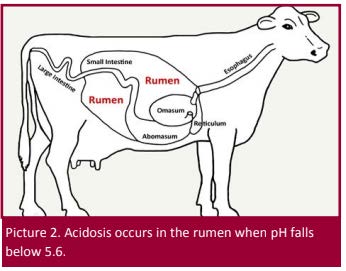

Acidosis

Symptoms of subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) include decreased feed intake, lower diet digestibility, and lower milk production and this can occur when the diet is overloaded with highly fermentable carbohydrates. Sugars are 100 percent digestible with starches coming in at a close second. Sugars and starches are rapidly fermented in the rumen and lower rumen pH. Acute acidosis occurs when the rumen pH is 5.0-5.2 or less and SARA between pH 5.2 and 5.6. In addition to sugar and starch, fiber also plays a role in rumen health.

Fiber and rumen balance

Fiber, which is the third classification of carbohydrates, has variable digestibility and can help manage rumen pH. In addition to being more slowly fermented in the rumen, fiber stimulates cud chewing which increases saliva production. Saliva acts as a buffer in the rumen to help maintain a healthy rumen pH and a balanced rumen microbial community. When nutrition causes an imbalance in the rumen, which can lead to hoof health issues.

Digital Dermatitis and Laminitis

There is a link between diet and hoof health. Research has shown that rapid increases in concentrates in the diet after calving increased the odds of having digital dermatitis (Somers, et al., 2005). During the high-grain feeding period in beef heifers, Treponema, Ruminobacter, and Lachnospiraceae species were found in the rumen (Chen et al., 2011). This is significant because research has suggested that bacteria or toxins can travel from the digestive system to other parts of the body (Oetzel et al., 2003) and Treponema bacteria are found in both the rumen after high grain feeding and in the hooves of cows with digital dermatitis infections. Furthermore, research has shown that inflammation can travel to different parts of the body. Acidosis causes damage and inflammation in the rumen, which can travel to the hoof and lead to laminitis (Shearer et al., 2011; Takahashi and Young, 1981). Therefore, proper ration balancing and feed management are very important in maintaining both rumen and hoof health.

Minerals and vitamins

In healthy animals, it is uncommon to see signs of vitamin or mineral deficiencies. However, cows developing acidosis can impair the rumen’s ability to metabolize and utilize vitamins and minerals properly.

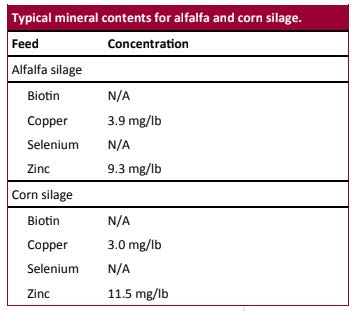

Minerals. Selenium helps protect cells against damage. There is not much research data about hoof health and supplemental selenium. However, it is reasonable to expect a healthier, more robust immune system in animals with sufficient dietary selenium levels compared to animals experiencing deficiency.

Zinc helps cows maintain a healthy immune system and supports proper metabolism. Both are critical, especially in cows with digital dermatitis infections or other lameness events.

Copper is needed to form strong connective tissue, including the laminae found in hooves. The laminae is important for moving and flexing the foot. If copper is deficient, signs include lameness and swelling of joints. It is very important to balance dietary copper and zinc because too much zinc prevents proper copper utilization and storage in the cow’s body.

Vitamins. Biotin, one of the B vitamins, is important in hoof health. Rumen microbes synthesize biotin and are sensitive to low pH. Acidosis can impair the microbes’ ability to make biotin. Providing 20 mg/day of supplemental biotin has been shown in research trials to health sole ulcers quicker (Lischer et al., 1996), reduce sole hemorrhages, (Bergsten et al., 1999), and reduce the incidence of interdigital dermatitis (Distl and Schmid, 1994).

General recommendations

According to the University of Minnesota, starch levels should be kept under 25 percent to help reduce the incidence of acidosis in the summertime. Diets should also contain at least 30 percent neutral detergent fiber (NDF), coming from high-quality forages. Use forages that have high NDF digestibility because it will help maintain energy intake. Dry matter intake typically drops as temperatures rise, so digestibility becomes especially important. A cow can only gain energy from feed that it can digest. Anything that is indigestible will end up in the manure. A Penn State Shaker Box can be used to gauge the fiber quality of the ration. There should be 8-12 percent of good consumable forage particles on the top screen of the shaker box. Consult with your nutritionist or county agent for specific nutritional recommendations.

Common issues

Changing the diet too quickly. Sudden dietary changes decrease rumen pH and cause an acidic rumen environment and a shift in microbial populations. Introducing diet changes slowly by making small increases or decreases over a period of time. For example, if the goal was to feed 20 percent of Feed X, then you might start by feeding 5 percent of Feed X. Once the cows have adjusted to this diet change, then you might increase Feed X to 10 percent and continue incrementally adjusting the diet until reaching 20 percent of Feed X. Keep in mind that these increments are merely to illustrate an example and are not intended to be used as recommendations. Consult with your nutritionist or county agent for specific recommendations.

Overloading the diet with sugars and starches. These are both highly fermentable which decreases rumen pH and creates an acidic environment. Be especially careful when changing concentrate levels in the diet and other ingredients with high sugar or starch concentrations. Consult with your nutritionist or Extension professional for specific recommendations.

Resources

Bergsten, C., P.R. Greenough, R.C. Dobson, and J. Gay. 1999. A controlled field trial on the effects of biotin supplementation on milk production and hoof lesions. J. Dairy Sci. 82(Suppl. 1): 34.

Chen, Y.H., G.B. Penner, M.J. Li, M. Oba, L.L. Guan. 2011. Changes in bacterial diversity associated with epithelial tissue in beef cow rumen during the transition to a high-grain diet. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 77:5770-5781.

Distl, O. and D. Schmid. 1994. Influence of biotin supplementation on the formation, hardness and health of claws in dairy cows. Tierarztliche Umschau 49:581-588.

Döpfer, D, K. Anklam, D. Mikheil, P. Ladell. 2012. Growth curves and morphology of three Treponema subtypes isolated from digital dermatitis in cattle. The Veterinary Journal. 193: 685-693.

Gressley, T. F. Inflammatory Response to sub-acute ruminal acidosis. University of Delaware, Department of Animal and Food Sciences.

“Hoof Anatomy, Care and Management in Livestock.” Purdue University. Accessed June 14, 2016. https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/id/id-321-w.pdf.

Lischer, C., A. Hunkeler, A. Geyer, and P. Ossert. 1996. The effect of biotin in the treatment of uncomplicated claw lesions with exposed corium in dairy cows. Proc. 9th Int. Symp. Dis. Rum. Digit. Jerusalem.

NRC. 2001. Nutrient requirements for dairy cattle (7th rev. ed.). N.A. Sci., ed., Washington, DC.

Oetzel, G.R. 2003. Subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cattle. Adv. Dairy Tech.. 15:307-317.

“Prepare now for summer feeding program.” University of Minnesota Dairy Extension. Accessed May 26, 2016. http://www.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/dairy/feed-and-nutrition/prepare-now-for-summer-feeding-program/.

Seymour, W.M. 2001. Biotin, Hoof health and milk production in dairy cows. 12th Ruminant Nutrition Symposium.

Shearer, J.K. 2011. Rumen acidosis, metalloproteinases, peripartum hormones and lameness. Pages 207-215 in proceedings of the 47th Eastern Nutrition Conference. Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Somers, J.G.C.J., K. Frankena, E.N. Noordhuizen-Stassen, J.H.M. Metz. 2005. Risk factors for digital dermatitis in dairy cows kept in cubicle houses in the Netherlands. Preventative Veterinary Medicine. 71:11-21.

Takashi, K. and B.A. Young. 1981. Effects of grain overfeeding and histamine injection on physiological-responses related to acute bovine laminitis. Jap. J. Vet. Sci. 43:375:385