Introduction

Automatic Milking Systems (AMS) 🔍 have revolutionized not only how cows are milked, but also how they are fed. In conventional milking systems, the feed bunk is the central point for delivering the cow’s complete daily nutritional needs. With AMS, however, a portion of a cow’s nutrients can be provided directly at the milking station, offering both new opportunities and challenges in individual nutrition management.

Regardless of the milking system, proper nutrition remains essential for controlling feed costs, optimizing efficiency, and supporting animal performance. While the core principles of nutrition and feeding still apply, AMS introduces unique factors that must be addressed.

This article explores how feeding at the AMS works, options for feed types, strategies for feed allocation and formulation, and bunk management.

Inside the Robot: How Cows Get Their Feed

How AMS Feeding Works

AMS units include an internal feeding station that dispenses feed to cows individually when they are in the milking stall. When a cow enters the unit and is deemed eligible for milking, a portion of feed is dispensed into the feed bowl 🔍 using an auger mechanism. This feed is commonly referred to as the AMS concentrate 🔍, AMS feed, robot feed, or robot pellet.

The amount of feed delivered is controlled by “Feed Tables 🔍“ within the AMS software. Feed tables enable farms to customize daily robot feed allowance based on cow-specific data such as milk production, peak milk yield, days in milk, and parity. Additional feed settings can be used to adjust the minimum and maximum amount of feed allowed per visit, feed dispensing speeds 🔍, and if amounts of unoffered feed from previous days can be carried over to the next day’s feed allocation.

Feed Delivery and Calibration

While feed tables assign feed amounts in pounds, AMS units do not actually weigh the feed as it is dispensed. Instead, they rely on “auger turns”. The AMS is calibrated to calculate how much feed is delivered with each auger rotation. At each AMS visit, the system uses the pre-calibrated feed weight per auger turn to dispense the correct amount of feed assigned to the cow. For this reason, accurate and routine calibration is critical. Regular calibration, recommended monthly, at each AMS feed delivery, or immediately after a significant feed change, ensures feed delivery remains accurate and consistent.

Currently, AMS units do not track whether cows consume all the feed dispensed during their milking. Unconsumed feed in the feed bowl may be consumed by the next cow, leading to inconsistencies in feed intake and inaccuracies in expected intake data. Checking feed bowls regularly can help identify if this becomes a recurring issue, which may indicate the AMS needs recalibration or that cows are being overfed at the robot.

Feed Type Options

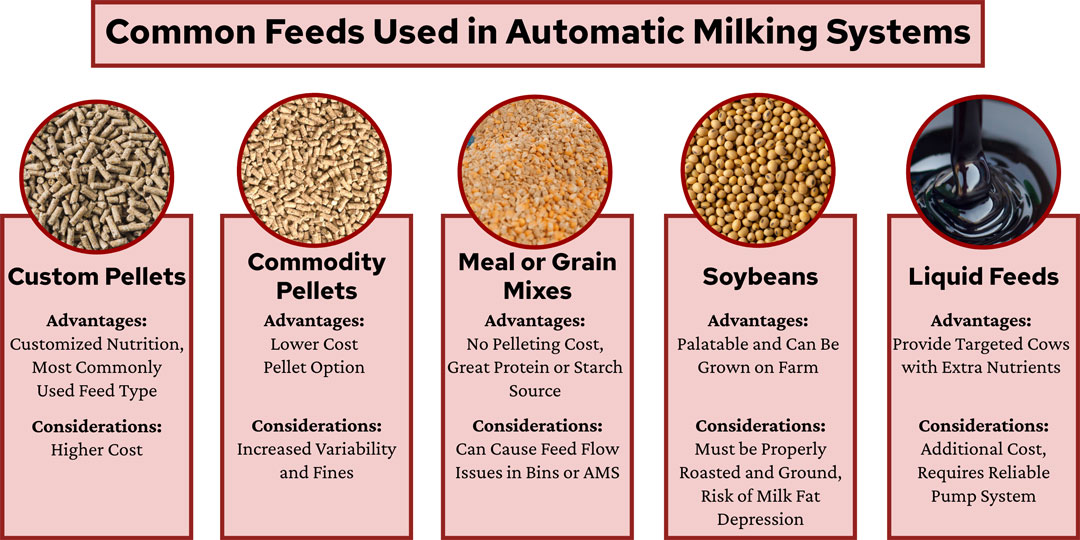

AMS units can deliver a variety of feed options, offering flexibility to meet nutritional and economic goals. Each feed option presents its own set of advantages and limitations. Generally, research suggests that cows prefer pelleted feed over other forms, such as meals or grains, which may influence AMS visit behavior and feed intakes (1, 2).

Common robot feed options include:

- Custom-Formulated Pellets

These pellets offer flexibility in formulation, allowing precise customization to meet farm goals. However, they tend to be more expensive than other options. - Generic Commodity Pellets

These feeds, such as corn gluten feed pellets, are generally more affordable than custom-formulated pellets, but don’t offer the ability to tailor the pellet for specific farm needs. They may also exhibit more variability between loads and create a higher percentage of fines. - Meal or Grain Mixes

Often a lower cost option, meals and grains can be a great source of protein or starch. Additionally, mixes may allow for customization. However, the fine texture of these feeds can cause bridging and funneling in bins or feed flow issues in the AMS. - Soybeans

Very palatable and potentially a low-cost option, especially when grown on-farm. However, improper roasting or grinding of soybeans can reduce digestibility. Additionally, feeding high levels of conventional soybeans can lead to milk fat depression. Feeding high-oleic soybeans can be considered as an alternative to conventional beans. - Liquid Feeds

When provided, liquid feeds are typically included as a secondary feed in the AMS targeted towards transition or high producing cows. These feeds can provide certain minerals, vitamins, and nutrients that supplement the standard AMS feed. These feeds require a reliable pump system to properly dispense the feed, especially in cold weather.

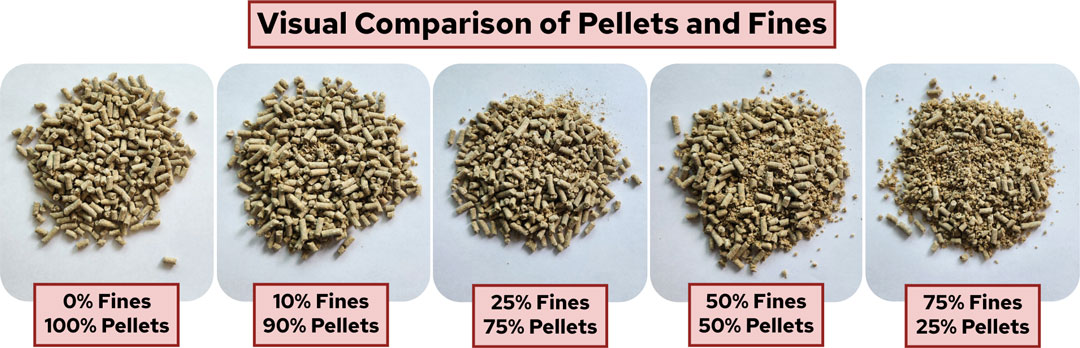

Importance of Pellet Quality and General Feed Consistency

Pellet durability is critical when feeding through Automatic Milking Systems. From production at the feed mill to delivery in the robot, pellets pass through multiple augers, bins, and environments. These factors can break down pellets and create fines. Increasing levels of fines have been associated with reduced feed intake, milking frequency and more fetch cows 🔍 (3). To perform well, pellets must be durable enough to withstand these challenges without crumbling.

Pellet quality depends on both formulation and the pelleting process. High-fat ingredients like meals or distillers’ grains tend to reduce pellet durability and should be limited in AMS feeds (4). In contrast, high-fiber ingredients such as wheat middlings can improve structural integrity and are often used in pellets.

Pellet durability can be evaluated using the Pellet Durability Index (PDI). In this test, a sample of pellets is weighed, subjected to physical agitation (e.g., tumbling or bouncing via air jets), and then re-weighed. PDI is calculated as the percentage of the final pellet weight relative to the initial weight. While no universal PDI standard exists, a value above 90% is generally recommended for AMS feeding to minimize fines and maintain consistency.

When feeding meals and grain mixes, consistency is critical. The density of individual ingredients may impact the blending of the mixes and flow through the bin. If separation of the mix occurs, cows may have inconsistent intakes of nutrients which can negatively impact milk production. As mentioned earlier, it’s important to routinely calibrate the AMS feed system and, when possible, visually inspect the feed in the bin.

Should You Flavor AMS Pellets?

The use of flavoring agents in AMS feed has been widely discussed. The assumption is that adding aroma or flavor will enhance palatability and encourage cow visits to the robot. However, research does not show consistent benefits from flavoring additives. In some cases, flavoring may be beneficial, but overall pellet ingredient palatability and using a hard, low-fines pellet appear to have a greater impact on cow performance in AMS herds. (5, 6, 7, 8).

Feeding Multiple Feeds

AMS units offer the ability to dispense multiple feeds 🔍, including liquids, allowing farms to implement more targeted nutrition strategies. For example, fresh cows may benefit from specific supplements while high-producing cows could be offered additional energy-dense feeds. While these tools offer exciting possibilities, formal research on multi-feed strategies in AMS remains limited. Implementing multiple feeds requires extra time, effort, and costs to manage multiple feed inventories, additional feed lines, and more complex feed tables. The system must also be capable of handling and dispensing the feed type, which can present challenges particularly with liquid feeds. Despite the limited research, some data suggest that offering multiple feeds may be associated with higher milk production per robot (9). This remains an evolving area, and further research is needed to define best practices for using multiple or liquid feed effectively in AMS systems.

How Much to Feed in the Robot

One of the most common questions in AMS nutrition is: How much concentrate should be fed at the robot? Unfortunately, there is no universal answer. The optimal amount varies widely based on individual farm conditions, including the types and availability of forages and concentrates. Key influencing factors include eating speed, barn design and traffic flow 🔍, type of concentrate used, the nutritional balance between the concentrate and PMR 🔍, and the individual needs of cows.

Eating Speed Can Limit AMS Feed Intake

The optimal amount of robot feed varies by farm, but cow’s eating speed sets a natural limit. Cows generally consume pellets at about 0.4 to 0.9 lb per minute, but this varies between individuals and feed types (10). For example, cows eat finely ground grains and meals more slowly than pellets.

Assuming an average of three milkings per day, each lasting about seven minutes, most cows can eat a maximum of 3 to 6.5 lb of concentrate per visit or 8 to 19 lb daily. Offering more feed than this per visit or day is not practical because the cow is simply unable to eat it all.

Over-allocating feed can also cause problems in diet formulation since it assumes cows will consume amounts of concentrate that they actually cannot. Research has found that as more concentrate is offered, the amount left uneaten increases (11). For this reason, it’s important to monitor feed closely and understand your cows’ actual concentrate eating speed to ensure the amount offered matches what cows can realistically consume.

Barn Traffic Influences Feed Allocation

Barn traffic design is a major factor in determining how much feed cows should receive at the robot.

- In free-flow systems 🔍, cows have unrestricted access to feed and stalls, so the feed at the robot becomes the main incentive for cows to visit. Research shows that cows are generally more motivated by feed than by being milked (12). Surveys report that free-flow barns typically feed between 9 and 15 lb of concentrate per cow per day on average. However, individual intakes vary widely – from 2 to 25 pounds per day – depending on visit frequency, diet formulation, and pellet type (13,14, 15).

- In guided-flow systems 🔍, cow movement is controlled, most often requiring cows to pass through a selection gate 🔍 prior to entering the AMS or feed bunk. In these systems, cows who meet eligibility for milking will be directed to the AMS and then to the feed area. Because of this, feed at the robot is less critical for encouraging visits and therefore feeding rates are usually lower. A Canadian survey found that guided-flow herds formulated to feed about 2 lb/cow/day less AMS concentrate than free-flow herds (13). Surveys typically report farms feeding 4-8 lb of concentrate per cow per day in guided-flow systems. Individual intakes ranged from 2 to 12 pounds depending on the farm. (13, 15, 16). Some guided-flow farms have experimented with feeding no concentrate at the robot, but this approach is not well-studied and requires high-level management.

Balancing the PMR and AMS Concentrate

While concentrate feeding is important in AMS herds, it’s crucial to remember that the partial mixed ration (PMR) still provides the majority of a cow’s daily nutrients. Success with AMS nutrition depends on a well-formulated PMR, built on high-quality forages, that supports cow performance. Robot concentrate should be seen as a complement to – not more important than – the PMR. Together they create a balanced diet that meets cow’s nutritional needs and encourages positive milking behavior in the AMS.

One strategy to achieving this balance is to distribute the total dietary energy supply appropriately between the robot concentrate and the PMR. Typically due to high starch content, feeding too much – or one that’s too energy dense – can drastically lower PMR intake, disrupt rumen function, and raise feed costs. Conversely, underfeeding concentrate may reduce robot visits, especially in free-flow systems, leading to more cows needing to be fetched for milking.

A common starting guideline is to balance the PMR for a milk production level about 15 pounds below the herd average. From there, adjustments can be made to further fine tune the ration. Free flow systems may need the energy content to be higher in the concentrate whereas in guided flow barns, distributing more of the energy into the PMR may be possible. (16, 17, 18).

As energy contribution is redistributed between the PMR and the robot concentrate, it is essential to consider how these changes impact total feed intake. Research shows that for every 1 lb average increase in consumption of AMS concentrate, cows tend to eat between 0.5 to 1.5 lb less PMR dry matter (18, 19). This trade-off should be considered during ration formulation. Additionally, feeding excessive concentrate through the robot is often neither nutritionally optimal nor cost-effective.

Feed Bunk Management in AMS Herds

Feed bunk management is just as important in AMS herds as in conventional farms. Research suggests that non-dietary management factors may explain up to 70% of the variation in dry matter intake and 55% of the variation in milk production across herds (11). This underscores the value of strong management practices that support dry matter intake and maintain healthy cows.

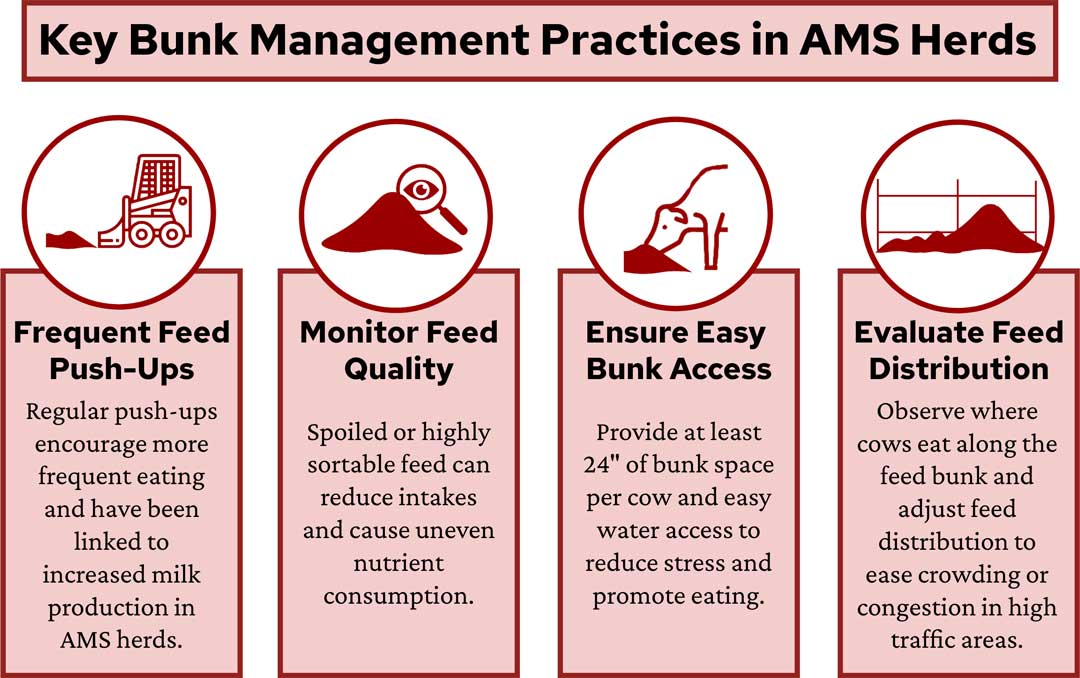

Key strategies for effective bunk management include:

- Frequent feed push-ups: Regularly pushing up feed, made easy with automatic feed pushers, has been linked to increased milking frequency and milk yield in AMS herds (20). A survey of AMS herds reported that on average, they pushed up feed 13 times per day (13).

- Ensuring cow comfort at the bunk: Providing adequate bunk space and water access reduces competition and stress, allowing cows to eat and drink comfortably which has been linked to improved milk production (21). A minimum of 24” of feed bunk space per cow should be provided (22).

- Monitoring feed quality and presentation: Watch for issues that can reduce intake, such as spoiled or heated feed, or highly sortable PMRs that lead to inconsistent nutrient consumption.

- Evaluate feed distribution along the bunk: Cows commonly visit the feed bunk after milking. Feed placed near the AMS exit may cause crowding and congestion. Observing where cows eat along the feed bunk throughout the day can help identify if feed distribution should be adjusted.

Conclusion

The flexibility of AMS feeding offers new opportunities to tailor diets at the individual cow level but also presents new challenges. Effective nutrition management in AMS requires a holistic approach that balances robot feeding with a well-balanced PMR and sound bunk management practices.

With attentive monitoring and proactive management in these areas, farms can maximize cow health and productivity while fully leveraging the benefits of AMS technology for precision feeding practices.

Katelyn Goldsmith

Dairy Outreach Specialist– In her role as a statewide Dairy Outreach Specialist, Katelyn connects research with practical farm management practices to create educational programming addressing the needs of Wisconsin dairy producers.

Published: December 5, 2025

Reviewed by: Gustavo Mazon Correa Alves (Cabrera Post-Doc) and Elizabeth French (USDA Dairy Forage Research Center, Research Animal Scientist)

References

- Johnson, J.A., Paddick, K.S., Gardner, M., & Penner, G.B. 2022. Comparing steam-flaked and pelleted barley grain in a feed-first guided-flow automated milking system for Holstein cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 105:221-230. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-20387

- Sporndly, E., & Asberg, T. 2006. Eating rate and preference of different concentrate components for cattle. Journal of Dairy Science, 89:2188-2199. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72289-5

- Rodenburg, J., E. Focker, and K. Hand. 2004. Effect of the composition of concentrate fed in the milking box on milking frequency and voluntary attendance in automatic milking systems. Pages 511– 512 in A Better Understanding of Automatic Milking. A. Meijering, H. Hogeveen, and C. J. A. M de Koning, ed. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, the Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.3920/9789086865253_128

- You, J., Tulpan, D., Krziyzek, C., & Ellis, J. 2025. Prediction of pellet durability index in a commercial feed mill using multiple linear regression with variable selection and dimensionality reduction. Journal of Animal Science, 103. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaf021

- Carroll, A.L., Buse, K.K., Stypinski, J.D., Jenkins, C.J.R., & Kononoff, P.J. 2023. Examining feed preference of different pellet formulations for application to automated systems. JDS Communications, 4:191-195. https://doi.org/10.3168/jdsc.2022-0318

- Carroll, A.L., Fincham, G.M., Buse, K.K., & Kononoff, P.J. 2024. Feed preference in lactating dairy cows for different pellet formulations. JDS Communications, 5:278-282. https://doi.org/10.3168/jdsc.2023-0517

- Migliorati, L., Speroni, M., Stelletta, C., & Pirlo, G. 2009. Influence of feeding flavouring-appetizing substances on activity of cows in an automatic milking system. Italian Journal of Animal Science, 8:sup2, 417-419. https://doi.org/10.4081/ijas.2009.s2.417

- Harper, M.T., Oh, J., Giallongo, F., Lopes, J.C., Weeks, H.L., Faugeron, J., & Hristov, A.N. 2016. Short communication: Preference for flavored concentrate premixes by dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 99:6585-6589. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11001

- Peiter, M., Irwin, E., Groen, B., Salfer, J.A., & Endres, M.I. 2019. Association of management practices, housing, milking speed, and robot visits with milk production per robot on free-flow automatic milking farm [Abstract]. American Dairy Science Association Annual Meeting, Cincinnati, OH. Access online at: www.adsa.org/Portals/0/SiteContent/Docs/Meetings/2019ADSA/2019ADSA_Abstract_Book.pdf?v20190715

- Kertz, A.F., Darcy, B.K., & Prewitt, L.R. 1981. Eating rate of lactating cows fed four physical forms of the same grain ration. Journal of Dairy Science, 64:2388–2391. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(81)82861-5

- Bach, A., & Cabrera, V. 2016. Robotic milking: Feeding strategies and economic returns. Journal of Dairy Science, 100:7720-7728. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11694

- Prescott, N.B., Mottram, T.T., & Webster, A.J.F. 1998. Relative motivations of dairy cows to be milked or fed in a Y-maze and an automatic milking system. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 57:23-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(97)00112-3

- Van Soest, B.J., Matson, R.D., Santschi, D.E., Duffield, T.F., Steele, M.A., Orsel, K., Pajor, E.A., Penner, G.B., Mutsvangwa, T., & DeVries, T.J. 2024. Farm-level nutritional factors associated with milk production and milking behavior on Canadian farms with automated milking systems. Journal of Dairy Science, 107:4409-4425. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-24355

- Salfer, J., Siewert, J., & Endres, M. 2018. Housing, management characteristics, and factors associated with lameness, hock lesion, and hygiene of lactating dairy cattle on Upper Midwest United States dairy farms using automatic milking systems. Journal of Dairy Science, 101:8586-8594. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-13925

- Siewert, J., Salfer, J., & Endres, M. 2018. Factors associated with productivity on automatic milking system dairy farms in the Upper Midwest United States. Journal of Dairy Science, 101:8327-8334. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-14297

- Endres, M., & Salfer, J. 2019. Feeding practices for dairy cows milking with robotic milking systems. Accessed online at https://dairy-cattle.extension.org/feeding-practices-for-dairy-cows-milked-with-robotic-milking-systems/

- Rodenburg, J. 2011. Designing Feeding Systems for Robotic Milking. Tri-State Nutrition Conference, Fort Wayne, Indiana, United States. Accessed online at http://www.dairylogix.com/Document-8.pdf

- Hare, K., DeVries, T.J., Schwartkopf-Genswein, K.S., & Penner, G.B. 2018. Does the location of concentrate provision affect voluntary visits, and milk and milk component yield for cows in an automated milking system? Canadian Journal of Animal Science, 98:399-404. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjas-2017-0123

- Schwanke, A.J., Dancy, K.M., Neave, H.W., Penner, G.B., Bergeron, R., & DeVries, T.J. 2022. Effects of concentrate allowance and individual dairy cow personality traits on behavior and production of dairy cows milking in a free-traffic automated milking system. Journal of Dairy Science, 105:6290-6306. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-21657

- Matson, R.D., King, M.T.M, Duffield, T.F., Santschi, D.E., Orsel, K., Pajor, E.A., Penner, G.B., Mutsvangwa, T., & DeVries, T.J. 2022. Farm-level factors associated with lameness prevalence, productivity, and milk quality in farms with automated milking systems. Journal of Dairy Science, 105:793-806. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-20618

- Deming, J.A., Bergeron, R., Leslie, K.E., & DeVries, T.J. 2013. Associations of housing, management, milking activity, and standing and lying behavior of dairy cows milking automatic systems. Journal of Dairy Science, 96:344-351. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-5985

- Dairyland Initiative. Automated Milking Systems. Accessed online at https://thedairylandinitiative.vetmed.wisc.edu/home/housing-module/adult-cow-housing/automated-milking-systems/