Introduction

Automated Milking Systems (AMS) are increasingly used in modern dairy operations as an alternative to conventional milking parlors. These systems allow cows to be milked voluntarily throughout the day, providing flexibility in milking frequency and herd management. Their adoption continues to rise steadily, with about 8% of US dairy farms currently using AMS and another 18% considering adoption (Hoard’s Dairyman, 2024). Successful implementation of AMS requires careful consideration of barn layout, cow traffic, and ventilation design. As AMS adoption expands, understanding facility design and operational requirements is critical for maintaining productivity and animal well-being.

Traffic Flow in AMS Barns

One of the first decisions when designing an AMS barn is selecting a cow traffic flow system. This refers to how cows move in the barn to access feed, stalls, and milking robots. The options include free flow, guided flow, or modified (hybrid) flow. Each approach has different implications for management and cow behavior.

In a free-flow system, cows have unrestricted access to the milking robots and feed. When a cow enters the robot, the entry gate closes if she meets the milking criteria (i.e., enough time has passed since her last milking) and she is milked. If not, the gate opens and she leaves without milking. She can then move freely within the pen, including to the stalls, feed bunk, or water trough, without being restricted by one-way gates.

The main reason cows visit the AMS in free-flow barns is the concentrated feed (pellets) dispensed at the robot. The advantage of the free-flow traffic is that it maximizes cow freedom. Cows are not forced to wait at gates, which helps reduce standing time in holding areas and promotes a more natural movement throughout the barn. The barn layout is also simpler and typically less expensive, with fewer adjustments required, which makes free-flow designs more feasible for retrofitting 🔎 existing barns.

In free-flow barns, it is often necessary to spend more time fetching 🔎 cows that do not voluntarily visit the robot. Without controlled traffic, some lower-ranking or less motivated cows may delay milking and need to be brought in. Additionally, since any cow can approach the robot at any time, the system needs to spend time identifying and releasing cows that are not due for milking, which reduces overall capacity. It was reported that free-flow systems, on average, produce slightly more milk per cow per day than guided-flow systems; however, this higher yield was linked to greater use of robot feed, which is more expensive than the total mixed ration (TMR) (The Dairyland Initiative, n.d.).

Overall, free-flow traffic provides cows with greater freedom but is generally better suited to barns with lower stocking densities.

In a guided-flow system, the movement of the cows is controlled by one-way gates. In this system, when a cow leaves the resting area, she passes through a selection gate 🔎 that detects whether she is due for milking based on the time since her last milking. If yes, it directs her into a holding area in front of the robots (commitment pen 🔎). After she is milked, she exits to the feeding area. If she is not yet eligible for milking, the selection gate allows her to go straight to the feed area instead.

One-way gates are designed so that cows cannot go from the stalls to the feeding area without passing through the selection gate, which means that a cow must “earn” access to feed by either getting milked or at least attempting to. This design relies on cows’ natural instincts to direct them through robots.

Guided flow offers several advantages compared to the free flow system:

- Fewer cows need to be fetched manually, saving time and labor.

- Cows without milking permission are blocked from entering the robot area, minimizing the number of rejections 🔎.

- Research shows that guided systems use fewer pellets per cow since cows are motivated by access to the feed bunk rather than just the robot pellet, cutting feed costs (Larson, 2014).

- After milking, cows can be automatically sorted into different pens or feeding areas based on production level or lactation stage.

However, guided systems have limitations:

- They require a layout that supports one-way gates, which may not fit in with the layout of all barns.

- The initial cost is higher due to the additional gates and infrastructure.

- Both cows and workers face a learning curve. Cows need to be trained to navigate through the gates.

- Timid or lower-ranking cows may avoid one-way gates or crowded areas, leading to long waits in the commitment pen or reduced access to feed. Prolonged standing and delayed feeding can increase the risk of health issues.

- One-way gates can make barn chores more difficult, especially when maneuvering equipment for tasks such as bedding or manure scraping.

In summary, guided flow gives more control to the owner, while free-flow offers more autonomy to the cows. Both can perform well under the right conditions.

A modified (hybrid) guided design is a compromise between the free and guided flow. Most AMS facilities are custom-designed hybrid barns. In this design, cows can move freely from the feeding area back to certain stalls without passing through gates, but they must use a one-way gate to access stalls in other areas. Water troughs are sometimes placed strategically to encourage cows to return to the resting area. Hybrid layouts simplify cow traffic patterns or accommodate retrofits while retaining some level of control. They require less fetching than free-flow systems while giving cows more freedom of movement than fully guided designs. The exact configuration depends on farm goals and the existing barn structure.

New Barn vs. Retrofit Barns

Farms can either build a new barn designed for AMS or retrofit an existing barn. An important part of planning involves determining the number of robots needed based on herd size.

Retrofitting an existing barn or building a new facility for AMS depends on the condition of the current structure and the associated costs. Retrofitting can be cost-effective if the barn already provides a good environment for cows, and infrastructure upgrades can be made without major compromises. However, if the existing barn has major flaws such as narrow alleys or a poor layout, a new barn would offer better long-term value. New construction allows for a fully customized design that supports efficient milking and future expansions.

Determining how many cows each robot will serve is a central planning decision that affects barn layout. A common recommendation is to have one robot per 60 to 80 cows to maintain consistent milking frequency.

For example, assuming that an average of 7 minutes is required to milk a cow and each cow is milked 2.8 times per day, a single robot would serve 63 cows daily. This corresponds to approximately 20.6 hours of robot operation time, leaving about 3.4 hours for cleaning, maintenance, and idle time 🔎. Recently, farmers aim to reduce the average milking time to under 6 minutes and eliminate idle periods. Rather than reserving a fixed downtime each day, the current system applies a recovery-time approach. If the robot stops for any reason, the subsequent hours are used to recover by temporarily increasing the expected milk yield required for milking permission.

Stocking too many cows per robot may lead to longer wait times, missed milkings, and increased stress. Factors such as milking speed 🔎, average yield, and traffic design affect robot capacity. Guided-flow systems support more cows by reducing waiting time, while free-flow systems often require a lower stocking rate to avoid cow traffic buildup.

It is also important to account for peak periods and special cases. When a large proportion of the cows are fresh cows, which typically requires longer milking times, the demand on the robots increases. To maintain consistent access and milking frequency, it would be wise to avoid sizing the system so tightly that small fluctuations in milking time or cow behavior exceed the available capacity. Pushing toward 80-85 cows may be feasible for some barns with low-maintenance cows and possibly guided flow, but it leaves less margin for fluctuations in milk production.

Using an Existing Parlor Alongside Robots

Some dairy operations gradually adopt robots or choose to milk only a part of their herd with robots while milking the rest of the cows using a conventional milking parlor.

A hybrid milking strategy can serve as either a transitional step or a long-term solution. One approach is to milk specific groups, such as fresh or high-producing cows, in the parlor while robots milk the rest. For example, rather than expanding the milking parlor, a farm could purchase two milking robots, continue milking 200 cows in the parlor, and assign the remaining 120-130 cows to the robots. This would increase milk production per robot by reducing its load. However, managing two systems requires additional scheduling, training, and maintenance, and it reduces the labor flexibility that automation typically offers. Some producers have found that complexity and duplicative costs outweigh the benefits and chose to transition to a single system.

Barn layouts

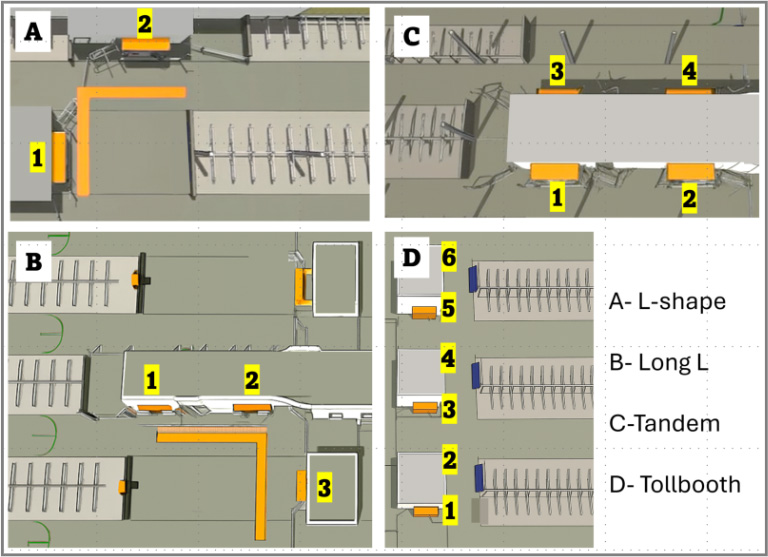

Some example AMS barn layouts are shown in Figure 1. A common configuration is the L-shape or long L-shape layout. In these designs, milking robots are positioned at an angle to the alley so that cow traffic is separated into incoming and outgoing lanes. This arrangement helps reduce cow traffic around the robots and can be especially useful in retrofitted barns. Depending on the pen size (120 or 180 cows), two or three robots can be assigned to each pen (Lely North America, 2019).

In the tandem design, robots are arranged in a line, one after the other. In the tollbooth design, robots are placed side by side, allowing a pen to have two or three robots, depending on the layout. This layout can accommodate larger herd sizes (Lely North America, 2019).

Ventilation Requirements in AMS Barns

Ventilating AMS barns is different from ventilating conventional barns due to factors such as the continuous presence of cows, traffic around the robots, and the equipment’s physical footprint. These conditions require ventilation strategies tailored to AMS barns.

24/7 Cow Presence and Traffic: In AMS facilities, cows are not taken to milking parlors, so the barn is occupied at all times, and heat, moisture, and gases are constantly produced. With no “empty barn” periods to purge barn air, the ventilation system needs to be designed to maintain consistent environmental conditions inside the building.

Cow Traffic Patterns Near Robots: Cows move to AMS units, often grouping around the robots and commitment pens as they wait their turn for milking. Inadequate ventilation in this high-traffic area can lead to warm and humid conditions.

Circulation fans directed toward the commitment pens are often used to prevent heat and gas buildup and to keep cows comfortable while waiting.

Robot Placement: AMS equipment, including robots, robot rooms, and gates, creates large physical obstacles that can block or redirect airflow. In naturally ventilated barns, attention should be paid to keep the airflow path from the sidewall inlets to the ridge vents clear, and equipment should be aligned parallel to the airflow when possible. In mechanically ventilated barns, robots should be placed strategically to avoid blocking air inlets. Ventilating parallel to robots can help reduce the size of wind shadows. Also, it should not be assumed that circulation fans can eliminate all stagnant air zones, as their effect can be limited (Mondaca, 2020).

Another important consideration is that if robots are placed far from the stalls, timid cows may be discouraged from using them. Robots should be located close to the stalls while also arranged to avoid blocking the airflow inside buildings.

Wider Barn Designs: If a barn is built wider to accommodate the robots, natural airflow may not effectively reach the center. In practice, farms with six to eight rows (100 to 120 feet) often find that natural ventilation is insufficient and switching to a mechanical system is the best solution (Akdeniz et al., 2025).

Cow Comfort in Milking Stalls

Cow comfort in the milking stalls supports higher milking frequency and reduces the number of fetch cows (Rodenburg, 2017).

- Rubber flooring and level entry improve access and encourage voluntary use.

- Fans above the robots help cool cows on warm days and reduce the number of flies in the milking area.

- Well-designed milking stalls allow cows to stand comfortably and remain calm during milking.

- Proper grounding is essential, especially since cows are in contact with metal components during milking.

Authors

Neslihan Akdeniz

Livestock Controlled Environments Extension Specialist, Assistant Professor– Mainly focusing on controlled environments for livestock production, also interested in nutrient management and indoor plant-growing facilities.

Douglas Reinemann

Milking Machine & Farm Energy, Cals Associate Dean for Extension – Douglas Reinemann is associate dean for extension and outreach in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences. As associate dean, he coordinates activities of CALS Extension faculty and academic staff with the Division of Extension, as well as outreach activities in the college. Dr. Reinemann is also a professor and Extension specialist in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering. His Extension programs are focused on machine milking, milk quality, and farm energy issues.

Published: January 16, 2026

Originally published in the November 2025 issue of Hoard’s Dairyman

Reviewed by:

- Katelyn Goldsmith, Outreach Specialist, Dairy and Livestock Program, UW-Madison Extension

- Carolina Pinzon, Bilingual Outreach Specialist, Dairy and Livestock Program, UW-Madison Extension

References

- Akdeniz, N., Bjurstrom, A., Schlesser, H. 2025. Natural Ventilation in Dairy Buildings. UW-Madison Extension. Online available at https://dairy.extension.wisc.edu/articles/natural-ventilation-in-dairy-buildings/ (1-8-2026).

- Endres, M., Salfer, J. 2019. Feeding Practices for Dairy Cows Milked with Robotic Milking Systems. DairExNet, online available at https://dairy-cattle.extension.org/feeding-practices-for-dairy-cows-milked-with-robotic-milking-systems/ (1-8-2026).

- Hoard’s Dairyman, 2024. Online available at https://hoards.com/article-35158-automated-milking-systems-gain-popularity.html (1-8-2026).

- Larson, G. 2014. Which Robotic Milking Traffic System Is the Best? Bullvine, online available at https://www.thebullvine.com/news/which-robotic-milking-traffic-system-is-the-best/ (1-8-2026).

- Lely North America. 2019. Top 5 barn designs for automated milking. Online available at https://youtu.be/_AHltLR7bpU (1-8-2026).

- Mondaca, M. 2020. Artex Barn Solutions. Online available at The Delicate Balance in Ventilating Robot Barns – YouTube (1-8-2026).

- Rodenburg, J. 2017. Optimal Design for AMS Barns. Online available at https://wcds.ualberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/57/2018/05/p-319-338-Rodenburg.pdf (1-8-2026).

- The Dairyland Initiative, n.d. Automated Milking Systems. Online available at https://thedairylandinitiative.vetmed.wisc.edu/adult-cow-housing/automated-milking-systems/ (1-8-2026).