Around the world exist a variety of domestic and non-domestic forage eaters called ruminants (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats, bison, buffalo, reindeer, yak, etc.). According to their geographic distribution, these species have diverse evolution histories that classified them by their capacity to adapt to different feed resources (Concentrate selectors, Intermediate feeders, and Roughage grazers). Ruminants play an important role in sustainable agricultural systems and as a provision of food to humans. They can convert forage, pasture crop residues, and other feed sources into food edible by humans. This situation has incited an interest in knowing the nutritional conditions and understanding the rumen development that makes them survive in their territories.

The stomach of the ruminant

The stomach of ruminants is made up of four compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. Each compartment has a very specific characteristic and function to help the digestion and absorption of essential nutrients to the animal. The rumen allows for the fermentation and digestion of forage type feeds. The reticulum acts as a sieve, moving smaller particles further down the digestive system and larger ones back into the rumen for further digestion. The omasum absorbs water and other substances from the digesta, and the abomasum breaks down proteins through acid digestion and functions similar to the human’s stomach.

Rumen development

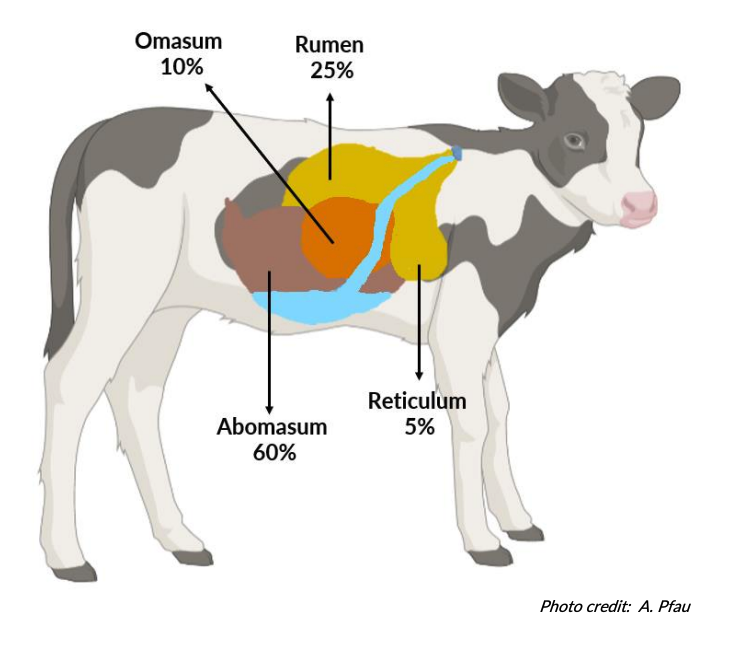

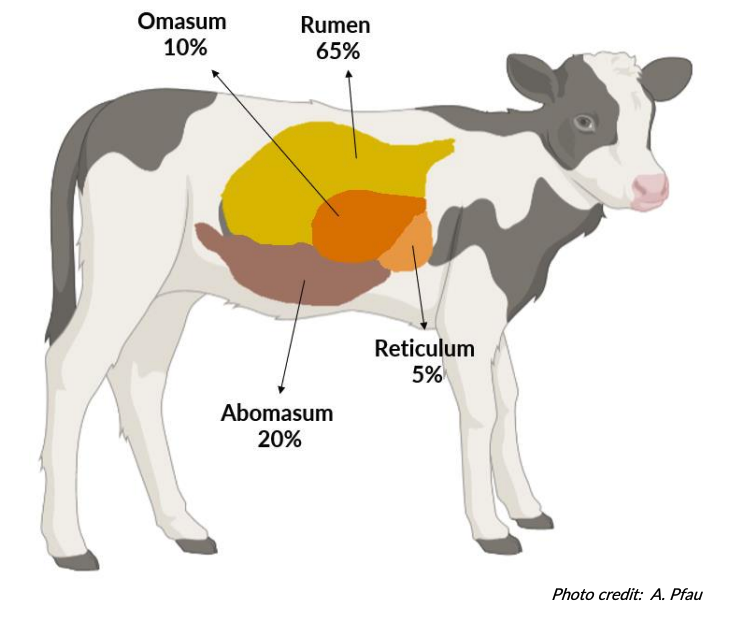

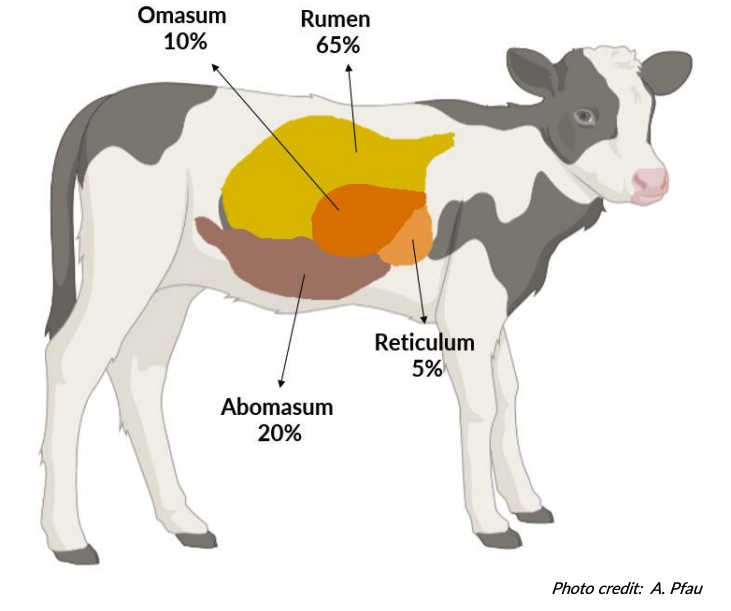

At birth, the dairy calf’s digestive system is underdeveloped. Different to cows, calves’ birth to 2 weeks of age are considered monogastric, or simple-stomached, due to a non-functioning rumen. The stomach of the calf contains the same four compartments mentioned above, but the reticulum, rumen, and omasum of the calf are inactive and underdeveloped. The only compartment that is active and functional is the abomasum which works similarly to the human’s stomach. This compartment represents 60% of the newborn calf’s stomach capacity and when the animal is mature, the capacity percentage of this compartment changes to just 8%. The capacity of the other compartments is 25% for the rumen, 5% for the reticulum and 10% for the omasum at birth and will change as the rumen develops to ferment and digest forages to 80%, 5%, and 8%, respectively.

With the help of the consumption of different feedstuffs and the growth and development of the calf, the stomach compartments also grow and change accordingly. At 4 weeks old, the calf continues to be fed milk or milk replacer as its main source of nutrition, and the growth in size of the abomasum increases. Because of the liquid diet and the digestion and absorption of milk in the abomasum, the rumen is not able to develop, remaining proportionately small and growing slower. Then, keeping a liquid diet (milk/milk replacer) for a long time will restrict rumen growth, affecting the development of the rumen not to develop to ferment and digest forages, thus decreasing the calf’s growth rates after weaning.

As the calf starts to eat dry feeds (starter grain) the rumen begins to ferment and break down the feed for digestion. The environmental conditions of the rumen favor the growth of microbes that break down the feed and produce byproducts called volatile fatty acids (VFAs): butyrate, propionate, and acetate. It is these byproducts, VFAs, that are absorbed through the lining of the rumen which helps to stimulate the rumen papillae growth, creating more surface area for nutrient absorption. Once the calf starts to eat more grain, by three weeks old, the rumen will establish enough bacteria to assist in the fermentation of feed to contribute a substantial amount of energy, and rumen microbial protein, a highly digestible protein similar to the protein profile of milk). The final stage of development occurs at weaning when the rumen becomes the most important part of the digestive system and allows the calf to digest forages and convert the feedstuffs into energy and protein.

Summary

It is necessary to understand the key features and purpose of the different sections and structures of the four compartments of the digestive system in calves. Each compartment is essential in maintaining a healthy digestive process and must work together efficiently to turn the calf’s feed into energy for the animal. Besides, the development of the rumen is fundamental in terms of efficiency and economy. In young calves starting with small amounts of grain along with water will start the fermentation process and the production of VFAs. This process in return develops a more functional rumen that can better digest grain, and later in life, this calf will become a high milk production cow that will digest forage and silage.