Table of contents

- Introduction

- Diet induced milk fat depression

- General Considerations

- Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) in Dairy Diets

- The Rumen Environment and Milk Fat Depression – Dietary Factors

- The Rumen Environment and Milk Fat Depression – Management Factors

- Milk Fat Depression Troubleshooting Questions

- Summary

- References

- Author

Introduction

Milk fat production is a key profit-driver for dairy farms, making it a focal point for producers and nutritionists. As the most variable milk component, herd-level milk fat percentage and yield are highly influenced by herd demographics, ration composition, and feeding management. Milk fat depression is commonly defined as a reduction in milk fat yield with no change in the yield of milk or other milk components (1). When milk fat depression (MFD) occurs, it can leave dairy producers questioning where to begin troubleshooting.

Diet induced milk fat depression

Diet induced milk fat depression hinges on two primary factors:

- An alteration in rumen pH leading to a shift in the microbial population

- A dietary source of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)

This article will explain these two factors, farm practices associated with them, and key questions to help you investigate and manage milk fat depression in your herd.

General Considerations

Understanding Milk Fat Depression Risk Factors

Managing risk factors associated with MFD is essential, but their presence does not necessarily mean a herd will experience the condition. In fact, some risk factors, when managed well, may not notably affect animal performance. However, when multiple risk factors begin to stack up, they can contribute to MFD. Rather than viewing risk factors in isolation, it is helpful to consider their combination along a spectrum, ranging from low to high risk. Formulating a ration that optimizes both milk production and energy often requires incorporating some risk factors, making careful management essential in preventing MFD.

Milk Fat Seasonality

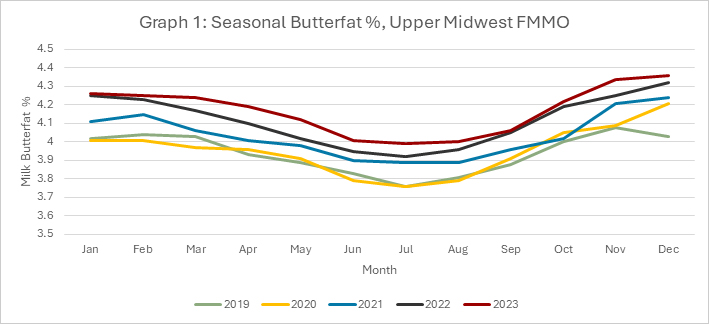

When evaluating if MFD is occurring in your herd, it is important to consider seasonal fluctuations in milk fat yield. National milk production data shows an annual rhythm in milk fat production, with peak yield occurring around January and varying by 0.15 to 0.30 percentage points throughout the year (2). Graph 1 displays the seasonal trend in milk fat production for the Upper Midwest Federal Milk Marketing Order which includes Wisconsin. With this in mind, changes in milk fat production should be evaluated in the context of your farms historical production data. Data from previous seasons should be used to set standards and goals for milk fat yield.

Upper Midwest Marketing Area Federal Milk Order No. 30. (3, 4, 5)

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) in Dairy Diets

PUFAs, naturally occurring in many feeds, can be toxic to fiber digesting bacteria. Fortunately, a subset of rumen microbes converts PUFAs to saturated fatty acids which are much safer for the rumen. This pathway is called biohydrogenation. However, when the system is overwhelmed with high PUFA levels, rumen bacteria shift from the normal pathway to an alternative pathway of biohydrogenation. This alternative pathway produces fatty acid compounds, such as conjugated linoleic acid, which inhibits milk synthesis (6).

Common ration ingredients containing high amounts of PUFAs include distillers’ grains, hominy feed, whole soybeans, and some bakery and candy byproducts. Corn grain portions of corn silage, high moisture corn, earlage, or snaplage can also contribute to dietary PUFA levels (7). If MFD occurs, evaluate your ration to determine if it contains high levels of PUFA-rich ingredients and consider reformulating it with lower PUFA alternatives.

The Rumen Environment and Milk Fat Depression – Dietary Factors

Optimizing diets for milk fat yield involves supporting the rumen microbial population and maintaining a stable rumen pH. Low rumen pH can trigger the alternative biohydrogenation pathway. This can be particularly detrimental if combined with high PUFA intake. Key dietary factors influencing rumen pH include starch levels, fiber content, and dietary buffers.

Starch

Excessive dietary starch has been shown to decrease milk fat content, likely from alteration of microbial populations and lowering rumen pH (8). This may result from high dietary starch content or multiple sources of rapidly digestible starch. Suggested dietary starch levels should be balanced, incorporating both rapidly digestible sources (i.e., high moisture corn) and slower-digesting sources (i.e., dry corn). Regularly test fermented starch sources to monitor starch digestibility, as it will increase over time during fermentation.

Fiber

Effective fiber is necessary to promote cud chewing and rumination, both of which help stabilize rumen pH. Saliva produced during cud chewing is the primary source of buffer for the rumen. Too little effective fiber can reduce cud chewing, rumination, and consequently, milk fat yield (9, 10). Use a Penn State Particle Separator to assess ration fiber content and particle length on farm. General guidelines for TMR particle size distributions are listed in Table 1. Keep in mind that effective fiber is not effective if cows are sorting it out. To monitor sorting, test samples with a Penn State Particle Separator immediately after feeding and periodically throughout the day. Cows will always sort feed to some extent, but the goal is to minimize it.

Recommended TMR Particle Size using the Penn State Particle Separator

(Table 1)

| Screen | Particle Size Inches | TMR % |

|---|---|---|

| Upper | >0.75 | 2 to 5 |

| Middle | 0.31 to 0.75 | > 50 |

| Lower | 0.16 to 0.31 | 10 to 20 |

| Bottom Pan | <0.16 | 25 to 30 |

Buffer

Supplemental dietary buffers help maintain rumen pH but are not meant to replace the buffering of saliva produced through healthy rumination. Buffer supplementation may be particularly beneficial in summer when cows lose more minerals and electrolytes through increased urination and sweating. Common buffer ingredients include sodium bicarbonate, sodium sesquicarbonate, and magnesium oxide. Buffers range in feeding rates and should be evaluated on a product-by-product basis when being added to rations.

The Rumen Environment and Milk Fat Depression – Management Factors

Feeding behaviors and management practices also play a significant role in maintaining rumen stability. Key factors to monitor include environmental stress, feed availability, and TMR uniformity.

Environment

Environmental stressors can include overcrowding and heat stress. Both scenarios will decrease cow’s laying time which is important for rumination and is correlated with feed intake, milk production, and milk component yield (12, 13). Ensuring a comfortable environment with adequate space and heat abatement can help sustain milk fat production.

Feed Availability

Slug feeding occurs when cows consume fewer, larger meals which can lead to drops in rumen pH. Instead, consuming smaller, more frequent meals has been associated with great milk fat production (14) To prevent slug feeding, focus on bunk management strategies including constant feed availability, regular feed push-ups, and evaluating feed delivery schedules to encourage smaller, more frequent meals. This is especially important during the summer months when cows may choose to eat during cooler parts of the day, resulting in fewer but larger meals instead of several small meals spread throughout the day.

Ration Mixing Uniformity

A well-mixed TMR ensures that all cows receive a consistent diet, regardless of where they eat along the bunk, minimizing fluctuations in nutrient intake. A ration may be formulated perfectly, but if mixed poorly, issues can still arise. Undermixing may in ingredients being unevenly distributed, leading to cows consuming an inconsistent ration. Overmixing can reduce the particle size of ingredients, decreasing the amount of physically effective fiber available. Assess mixing uniformity with a Penn State Particle Separator. Collect multiple feed samples along the bunk, especially from the beginning and end of a load. If significant variability appears, review and adjust mixing protocols to improve consistency.

Regularly monitoring the dry matter (DM) content of forages is also important. The DM content of forages is essential for calculating the proper amount to add when mixing a TMR. If the DM content changes and the ration is not adjusted accordingly, issues can arise – such as feeding less physically effective fiber than intended. Forage DM can be tested through lab analysis or on-farm using a Koster tester, air fryer, microwave, or food dehydrator.

Milk Fat Depression Troubleshooting Questions

When faced with milk fat depression, identifying the cause can sometimes feel like a mystery. Use these questions to begin your investigation and guide your next steps. Dialing in your ration, management, and environment will help stabilize and improve milk fat production.

- Does my ration contain high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids?

- What is my rations starch concentration? How digestible is the starch in my ration?

- Does my ration provide enough physically effective fiber?

- Am I providing adequate amounts of buffer in the ration?

- Is my ration sortable? Is the ration being uniformly and consistently mixed?

- Are my cows experiencing stressors that may affect feed intake? Are they overcrowded, heat stressed, or running out of feed?

Summary

By systematically evaluating ration composition, feeding management, and environmental factors, you can take proactive steps to stabilize and improve milk fat production in your herd.

References

- Bauman, D. E., & Griinari, J. M. (2001). Regulation and nutritional manipulation of milk fat: lot-fat milk syndrome. Livestock Production Science, 70(2001), 15-29. doi:10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00195-6

- Salfer, I.J., Dechow, C.D., & Harvatine, K.J. (2019). Annual rhythms of milk and milk fat and protein production in dairy cattle in the United States. Journal of Dairy Science, 102:742-753. Doi:10.3168/jds.2018-15040

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service (2020). Compilation of Statistical Material 2018-2019. http://www.ffma30.com

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service (2022). Compilation of Statistical Material 2020-2021. http://www.ffma30.com

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service (2024). Compilation of Statistical Material 2022-2023. www.ffma30.com

- Bauman, D.E., Harvatine, K.J., & Lock, A.L. (2011). Nutrigenomics, rumen-derived bioactive fatty acids, and the regulation of milk fat synthesis. Annual Review of Nutrition, 31:299-319. Doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104648

- NASEM. (2021). Nutrient requirements of dairy cattle: eighth revised edition. Washington, DC: The National Academics Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25806

- Jenkins, T.C., & McGuire, M.A. (2006) Major advances in nutrition: impact on milk composition. Journal of Dairy Science, 89:1302-1310. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72198-1

- Beauchemin, K.A., & Zang, W.Z. (2005). Effects of physically effective fiber on intake, chewing activity, and ruminal acidosis for dairy cows fed diets based on corn silage. Journal of Dairy Science, 88:2117-2129. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72888-5

- Zebeli, Q., Dijkstra, J., Tafaj, M., Steingass, H., Ametaj, B.N., & Drochner, W. (2008). Modeling the adequacy of dietary fiber in dairy cows based on the responses of ruminal pH and milk fat production to composition of the diet. Journal of Dairy Science, 91:2046-2066. doi:10.3168/jds.2007-0572

- Grant, R.J., & Cotanch, K.W. (2022). Perspective and commentary: Chewing behavior of dairy cows: Practical perspectives on forage fiber and the management environment. Applied Animal Science, 39:146-155. doi:10.15232/aas.2022-02371

- Woolpert, M.E., Dann, H.M., Cotanch, K.W., Melilli, C., Chase, L.E., Grant, R.J., & Barbano, D.M. (2017). Management practices, physically effective fiber, and ether extract are related to bulk tank milk de novo fatty acid concentration on Holstein dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science, 100:5097-5106. doi:10.3168/jds.2016-12046

- McWilliams, C.J., Schwanke, A.J., & DeVries, T.J. (2022). Is greater milk production associated with dairy cows who have a greater probability of ruminating while laying down?, JDS Communications, 3:66-71. Doi:10.33168/jdsc.2021-0159.

- Johnston, C., & DeVries, T.J. (2018). Short communication: Associations of feeding behavior and milk production in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 101:3367-3373. doi:10.3168/jds.2017-13743

Author

Katelyn Goldsmith

Dairy Outreach Specialist– In her role as a statewide Dairy Outreach Specialist, Katelyn connects research with practical farm management practices to create educational programming addressing the needs of Wisconsin dairy producers.