Types of Liver Flukes

Cattle herds in Wisconsin face ongoing challenges from two species of liver flukes—Fasciola hepatica (the common liver fluke) and Fascioloides magna (the deer liver fluke). These parasitic flatworms can cause significant liver damage, reduce animal productivity, and increase the risk of secondary infections, such as Redwater Disease. Although both types are found in the state, deer liver flukes are more common in pastures with high deer activity, which increases the risk to grazing cattle.

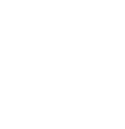

Life Cycle of Liver Flukes

Fasciola hepatica (the common liver fluke) undergoes a complex lifecycle involving freshwater snails (typically Lymnaeid snails) as intermediate hosts. Eggs are shed in feces and hatch in aquatic environments, eventually infecting snails and developing into a free-swimming larval stage (cercariae). These free-swimming larvae attach to aquatic vegetation, form hardy cysts (metacercariae), and are later ingested by ruminants. Once inside the host, they migrate from the intestines to the liver, where they mature in the bile ducts and begin laying eggs, completing the cycle.

(Figure created by Carolyn Ihde and Heather Schlesser using Canva and BioRender)

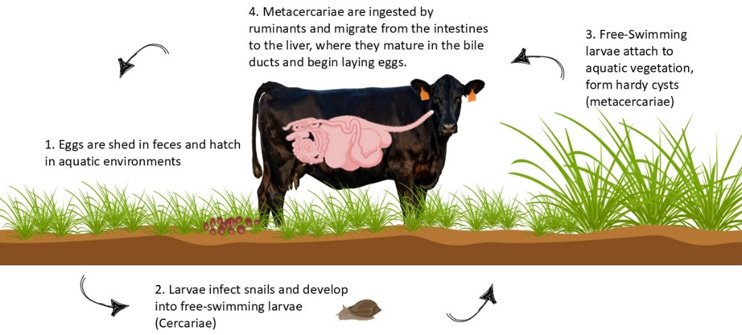

Fascioloides magna, on the other hand, follows a similar pattern but

behaves differently in cattle. Since cattle are not the parasite’s

natural host, they don’t shed infectious eggs, making them a “dead-end” host. Unfortunately, that doesn’t spare them from harm: the flukes encyst in the liver, cause severe tissue damage, and can lead to secondary infections, including life-threatening Redwater Disease.

(Figure created by Carolyn Ihde and Heather Schlesser using Canva and BioRender)

Redwater Disease

Redwater Disease is caused by the bacterium Clostridium haemolyticum, which can lie dormant in healthy animals. When liver damage occurs—such as from fluke migration—these spores can become active, releasing toxins that destroy red blood cells—the result: anemia, sudden illness, and often death if left untreated.

Monitoring

To determine if liver flukes are present in your herd, diagnostic testing is essential. Collect fecal samples from at least 20 animals for submission to a diagnostic lab. Be sure to specify that you want the lab to screen for liver fluke eggs, as routine fecal tests typically detect only common gastrointestinal parasites. Without this specific request, fluke infections can go undetected. It is important to keep in mind that fecal egg testing will only determine if your herd has been exposed to F. Hepatica, as eggs from F. Magna are encapsulated in the liver and not shed.

Liver Fluke Mitigation and Treatment Strategies

Controlling fluke exposure begins with interrupting the life cycle. The life cycle can be interrupted by minimizing cattle access to snail habitats, or wet, marshy areas. Strategies include:

- Fencing off low-lying or marshy zones

- Installing drainage systems

- Avoiding high-risk pastures during peak infection windows

- For treatment:

- F. hepatica infections respond to clorsulon, found in combination injectable products like Ivomec Plus and Bimectin Plus.

- F. magna, however, is not susceptible to clorsulon. Treatment requires albendazole (Valbazen), but with caveats—it’s only effective against adult flukes (over 90 days old) and is not recommended for early gestation.

In Wisconsin, timing treatment 12–15 weeks after the first killing frost is often advised. Treating at this time ensures flukes have matured enough for albendazole to be effective and coincides with snail dormancy, interrupting future infections. In heavily infested areas, a second dose may be warranted 90 days after the initial treatment to catch any immature flukes that were not killed at the first treatment. Ensure you follow the label instructions and consult with your veterinarian to determine the proper dosing and treatment protocols.

A Proactive Approach

No control program is foolproof. Even with diligent pasture management and treatment timing, residual liver damage may occur, leaving cattle vulnerable to further illness. If deer flukes are suspected in your area, it’s worth speaking with your veterinarian about incorporating a Clostridium haemolyticum vaccination into your herd health protocol.

Author

Heather Schlesser

County Dairy Educator – Heather Schlesser is an Agriculture Educator in Marathon County. Heather’s research and outreach have included the use of current technology to enhance farm profitability and sustainability. Her current projects include the Animal Wellbeing Conference, the Midwest Manure Summit, Beef Quality Assurance, financial programming, and teaching farmers throughout the Midwest how to breed their own cattle.

Reviewers

Carolyn Ihde

Small Ruminant Outreach Specialist

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Division of Extension

Beth McIlquham

Regional Livestock Educator

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Division of Extension

References

- Liver Flukes in Michigan. Grooms, D.(2007), Veterinary Extension. Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine. https://web.archive.org/web/19981205212135/http://cvm.msu.edu/extension/docs/flukes.htm. accessed: 4/19/2007.

- Liver Flukes in Missouri : Distribution, Impact on Cattle, Control and Treatment. Payne. Craig A., and Delaney, Lauren E. (2022). University of Missouri Extension. https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g2119

- Liver flukes and redwater disease in Minnesota beef cattle. Mousel, Eric, Schefers, Jeremy, and Goldsmith, Tim. (2021). University of Minnesota Extension. https://extension.umn.edu/beef-cow-calf/liver-flukes-and-redwater-disease-minnesota-beef-cattle

▶️ Watch: Biosecurity During a Disease Outbreak

▶️ Watch: Biosecurity During a Disease Outbreak ▶️ Watch: Disease Basics An Overview of Bovine Leukemia Virus

▶️ Watch: Disease Basics An Overview of Bovine Leukemia Virus Managing Internal Parasites in Cattle

Managing Internal Parasites in Cattle Thanks for Your Deworming Management

Thanks for Your Deworming Management