Introduction

Colostrum is an essential source of nutrients, antibodies, and growth factors that set calves up for a strong start to life. Years of research have consistently shown the most critical management factor for calf health and survival is providing early, adequate volumes of high-quality colostrum.

Despite this, many farms experience a common issue that leaves farmers and calf managers scratching their heads – declines in colostrum production during the fall and winter months. This problem can make it difficult to quickly feed calves high quality colostrum in adequate quantities.

This article will discuss potential causes for the seasonal colostrum “slump,” ways to promote colostrum production, and how to manage through periods of low colostrum production.

Photoperiod, Temperature, and Colostrum

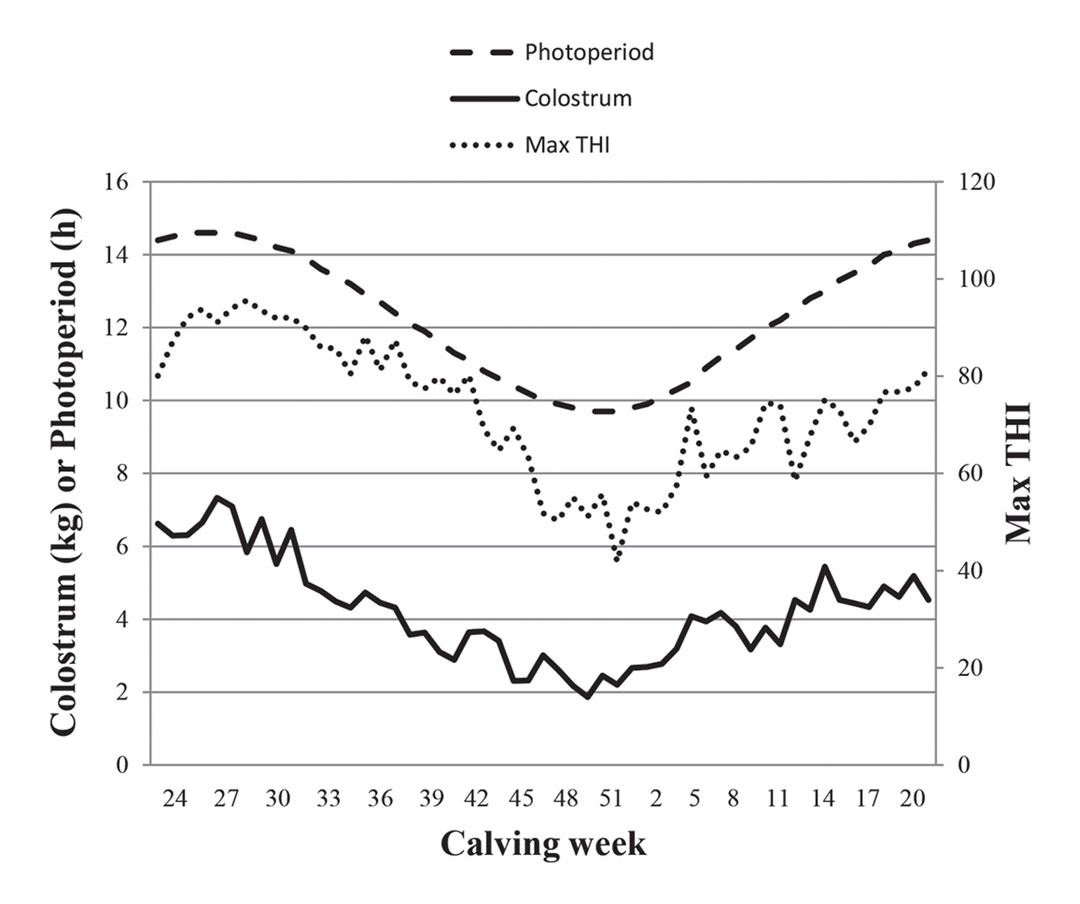

In the last decade, more research has focused on uncovering why colostrum production drops in the fall and winter months. While multiple factors seem to play into this phenomenon, researchers have discovered a relationship with photoperiod and temperature-humidity index (THI). Photoperiod, simply defined as daylight length, begins decreasing in late June and reaches its shortest length in December. In addition, THI, a measure of heat and humidity exposure, is greatest in the summer months. These two factors together have been associated with colostrum yield.

A study by Gavin and colleagues in Texas examined a herd of approximately 2,500 cows to better understand factors affecting colostrum yield (1). Over the year-long study, they found that average colostrum yield per cow was highest in June at 6.6 kg (14.5 lb), and lowest in December at 2.5 kg (5.5 lb). Additionally, they noted that cows in their second or later lactation experienced a greater seasonal decline in colostrum yield than first-lactation cows. They observed that shorter photoperiod length and lower THI were significantly associated with lower yields.

Graph created by Gavin and colleagues (1).

Similarly, a 2022 study from Cornell University looked at data from approximately 19,000 cows across 19 New York dairies to evaluate factors affecting colostrum production (2). Their findings confirmed that cows’ daylight and THI exposure prior to calving was associated with colostrum yield. Exposure to less daylight and lower THI was correlated with lower yield. But even between these herds that shared a common geographic area (and therefore similar daylight and THI), variability in yields was observed. This suggests that photoperiod and THI play an important role in colostrum production, but other factors also likely contribute (3).

Other Contributing Factors

Although photoperiod and THI appears to play a significant role in seasonal declines of colostrum production, other influencing factors have been noted. A review published in 2023 highlighted several other items associated with colostrum yield (3). These include dry period length, calf birth weight, whether the calf was born alive, and the cow’s milk production in the previous lactation. Research on nutrition’s impacts on colostrum yield has produced mixed results. A review conducted by researchers at the University of Guelph reported that adjusting protein, carbohydrate, or fat levels in dry cow diets did not consistently affect colostrum production and quality (4). This suggests that while feeding a nutritionally sound diet is undoubtedly important, feeding excessive nutrients beyond requirements may not prove beneficial. Instead, other factors such as photoperiod and stress during the transition period may play a larger role in promoting colostrum yield during seasonal slumps.

Promoting Colostrum Production

Despite the challenge posed by shorter days and lower THI in the fall and winter, there are steps that farmers can take to support colostrum production:

- Dry Period Length: Ensuring cows have an adequate dry period is beneficial for colostrum production. Cows with short dry periods produce lower yields of colostrum (5). 45–60-day dry periods are considered ideal.

- Minimize Environmental Stressors: Dry cows should have consistent and adequate access to feed and water. Limited or restricted feed and water access can reduce dry matter intakes, negatively affecting colostrum production.

- Encourage Colostrum Let Down: During milking, maintain a calm and low-stress environment. Ensure that cows are properly prepped prior to attaching milking units and that they are completely milked out before unit removal. Colostrum quality decreases when harvest is delayed. For best quality, harvesting colostrum less than 8 hours post-calving is recommended (3, 5).

- Consider Oxytocin for First-lactation Cows: Administering oxytocin has been shown to promote colostrum let down and increase yield in first-lactation cows. Recent research found that first-lactation cows produced 1.6 kg (3.5 lb) more colostrum when administered an appropriate dose of oxytocin compared to untreated cows (6). If considering this route, farmers should discuss with their veterinarian if using oxytocin fits with their operation.

- Assess Feed Additives: Some recent studies have found feed additives such as choline or calcidiol in dry cow diets have improved colostrum yields (7, 8). When evaluating feed additives, ensure they are research-backed products that have been assessed for their impact on colostrum production.

Managing Colostrum Supply

When experiencing low colostrum supply, there are ways to manage through it and ensure your calves get the nutrients they need:

- Build a Colostrum Bank: A well-stocked colostrum bank can be a lifesaver during periods of low production. Use a tool such as a Brix refractometer to assess colostrum quality and store it accordingly. For example, high quality colostrum with a Brix value greater than 22% can be reserved for heifer calves, while lower quality colostrum can be used for bull calves. This colostrum can then be stored for later use.

- Follow Proper Storage Practices: Colostrum should be refrigerated for no more than 1 day or frozen for up to a year to maintain quality (9). Properly label colostrum and store it in a clean environment to prevent contamination.

- Have Colostrum Replacer Available: In cases when colostrum is unavailable or is poor quality, have a quality colostrum replacer ready. Select a replacer (not supplement) that will provide newborn calves with 300 grams of immunoglobulin G (IgG). This is the gold standard set by the Dairy Calf and Heifer Association.

Summary

Although seasonal declines in colostrum production can be a frustrating challenge, it can be successfully managed with the right preparation and protocols. With the right approach, you can ensure your calves receive the colostrum they need and have a strong start.

Authors

Katelyn Goldsmith

Dairy Outreach Specialist– In her role as a statewide Dairy Outreach Specialist, Katelyn connects research with practical farm management practices to create educational programming addressing the needs of Wisconsin dairy producers.

References

- Gavin, K., Neibergs, H., Hoffman, A., Kiser, J.N., Cornmesser, M.A., Haredasht, S.A., Martinez-Lopez, B., Wenz, J.R., & Moore, D.A. 2018. Low colostrum yield in Jersey cattle and potential risk factors. Journal of Dairy Science, 101:6388-6398. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-14308

- Westhoff, T.A., Womack, S.J., Overton, T.R., Ryan, C.M., & Mann, S. 2022. Epidemiology of bovine colostrum production in New York Holstein herds: Cow, management, and environmental factors. Journal of Dairy Science, 106:4874-4895. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22447

- Westhoff, T.A., Borchardt, S., & Mann, S. 2023. Invited review: Nutritional and management factors that influence colostrum production and composition in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 107:4109-4128. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-24349

- Hare, K.S., Fischer-Tlustos, A.J., Wood, K.M., Cant, J.P., & Steele, M.A. 2023. Prepartum nutrient intake and colostrum yield and composition in ruminants. Animal Frontiers, 13:24-36. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfad031

- Godden, S.M., Lombard, J.E, & Woolums, A.R. 2019. Colostrum management for dairy calves. Vet Clin Food Anim, 35:535-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2019.07.005

- Mann, S., Bruckmaier, R.M., Spellman, M., Frederick, G., Somula, H., & Wieland, M. 2024. Effect of oxytocin use during colostrum harvest and the association of cow characteristics with colostrum yield and immunoglobulin G concentration in Holstein dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science, 107:7469-7481. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2024-24909

- Swartz, T.H., Bradford, B.J., Malysheva, O., Caudill, M.A., Mamedova, L.K., & Estes, K.A. 2022. Effects of dietary rumen-protected choline supplementation on colostrum yields, quality, and choline metabolites from dairy cattle. JDS Communications, 3:296-300. https://doi.org/10.3168/jdsc.2021-0192

- Martinez, N., Rodney, R.M., Block, E., Hernandez, L.L., Nelson, C.D., Lean, I.J., & Santos, J.E.P. 2017. Effects of prepartum dietary cation-anion difference and source of vitamin D in dairy cows: Lactation performance and energy metabolism. Journal of Dairy Science, 101:2544-2562. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-13739

- Dairy Calf and Heifer Association Gold Standards. 3rd Edition. Dairy Cal and Heifer Association, New Prague, MN.

The University of Wisconsin–Madison Division of Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming in compliance with state and federal law.