English | Español

Introduction

Fiber is an important part of dairy cattle diets and much confusion exists surrounding the different types of fiber found in common diet feedstuffs and how they can be leveraged in a well balanced diet. Fiber is a type of carbohydrate and successful inclusion in the diet supports overall cow health and productivity. This article will break down the different types of fiber and how each supports milk production.

Carbohydrates and Fiber in Dairy Cattle Diets

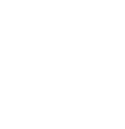

Carbohydrates in ruminant diets can be split into two major types: non-structural carbohydrates (NSC), and structural carbohydrates. Non-structural carbohydrates, include sugar, starch, and other cell substances that make up the internal contents of plant cells. They are easily digested by rumen microorganisms, providing the cow with a quick source of energy. On the other hand, structural carbohydrates are part of the plant cell wall and are responsible for structural support, nutrient transportation, cell protection and shape. When discussing fiber, we are typically focused on the structural carbohydrate portions of the feedstuffs. And this is where things get challenging. There are many different ways that we refer to the different fiber fractions found in feeds.

Types of Fiber

Effective Fiber

Effective fiber is the portion of fiber that stimulates chewing and saliva production and depends on the diet’s particle size. Feeding only small particles (0.16-inch or less) will cause fast passage rate through the rumen and can trigger acidosis but feeding only large particles (larger than 0.31 inch) will decrease milk production due gut fill resulting in a lack of energy and very slow feed passage rate.

Some larger fiber particles or “physically effective fiber” (larger than 0.31 inch)—such as those found in hay and straw—are necessary, and have a beneficial impact on rumen function. In the right amount, large particles stimulate rumen contractions, increase saliva production, and support milk fat synthesis. In contrast, the lack of effective fiber can result in digestive disorders, such as acidosis and milk fat depression. To evaluate the content of physically effective fiber in a ration, farmers can use the Penn State Particle Separator. ↗️

Fiber from a lab test

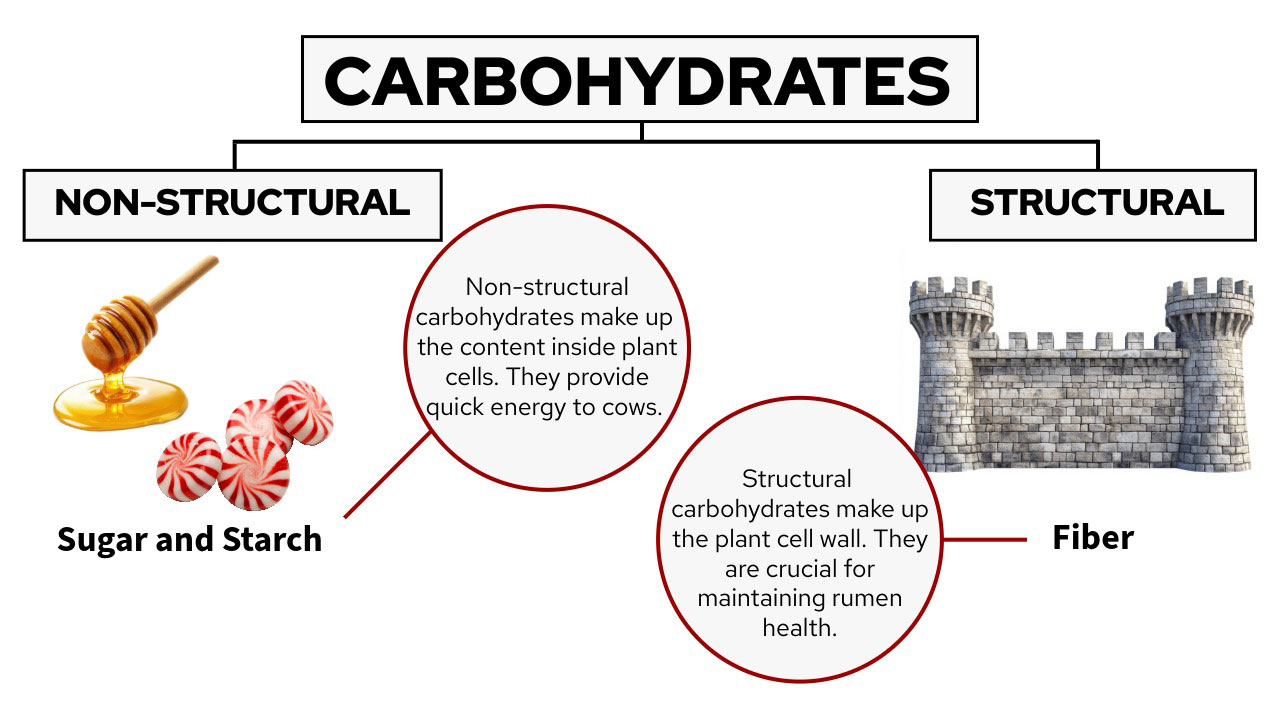

When sending samples for lab analysis, the fiber results are presented as Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), and Lignin.

Image created with BioRender.com

- Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), is a measure of the three main cell wall components (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin). In general, when the NDF value of a feed is too high, it means that feed takes up greater space in the rumen and is slowly digested, which could lead to a decrease in dry matter intake.

- Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), measures the cellulose and lignin content.These two components are less digestible than hemicellulose. This value can be used as a metric for digestibility. If a large portion of the forage’s fiber is ADF, it will not be as digestible and will provide less energy to the cow compared to a forage with a lower ADF value.

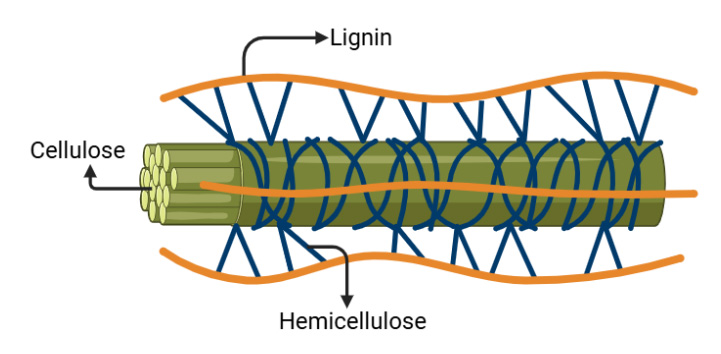

- Lignin is an indigestible cell wall component that provides structural support to plants, helping them remain upright as they grow. As forages mature, lignin content increases to support the larger plant, but this effect reduces overall digestibility. This highlights the importance of harvesting forages at the proper stage of maturity to optimize yield and digestibility. Some forage varieties, such as BMR corn and low-lignin alfalfa, have been selectively bred or engineered to contain less lignin and improve digestibility.

| Early Harvest Less Mature |

Late Harvest More Mature |

|

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall | Thinner | Thicker |

| NDF | Lower | Higher |

| ADF | Lower | Higher |

| Lignin | Lower | Higher |

| Effective Fiber | Lower | Higher |

| Intake (Dry Matter) | Higher | Lower |

| Energy available | Higher | Lower |

Insoluble and soluble Fiber

Insoluble fiber refers to three components of the plant cell wall we have already talked about—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—that do not dissolve in the solution used in the Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF) method. These components are not easy to digest by cows. However, the cell wall also contains a soluble part made up of digestible carbohydrates, such as pectins, fructans, beta-glucans, and even some resistant starches, those are what we refer as soluble fiber.

Conclusion

While structural carbohydrates do take longer to break down in the rumen, they are also the main components of dietary fiber and provide many important benefits in dairy cattle diets, including:

- Stimulating rumination. Longer forage particles stimulate the cow to regurgitate and chew their cud. This prompts saliva production. Saliva buffers the rumen to help maintain a healthy pH, around 6.2.

- Supporting rumen microbial health. The rumen is populated with microorganisms that aid in digesting feed and its nutrients. These microbes function best within a stable pH range. Fiber consumption helps boost rumination to maintain the rumen at a healthy level that supports optimum microbial activity.

- Preventing digestive issues such as bloat or displaced abomasum (DA). When we maintain rumen microbe health, it promotes the health of the entire ruminant digestive tract. Effective, longer stem fiber particles create rumen fill that can help prevent DA occurrence. Bloat can occur when cattle consume high levels of non-structural carbohydrates, so maintaining appropriate fiber levels reduces these incidences.

- Acetate (or acetic acid) production. This volatile fatty acid (VFA) is an important energy source for the cow and supports butterfat production. Butterfat depression is often combated by properly balancing fiber in the diet.

Understanding the different types of fiber and measuring fiber content through tools like the Penn State Particle Separator or lab analyses such as NDF, ADF, and Lignin content, allows farmers to make informed decisions about forage quality and feeding strategies. As plants mature, fiber content (particularly lignin content) increases, reducing digestibility and energy availability. Therefore, managing harvest timing and selecting appropriate forage varieties are key to optimizing both intake and milk production. Supplying the right type and amount of fiber is not just about filling the cow—it’s about fueling her efficiently and keeping her healthy and productive.

Authors

Manuel Peña

Regional Dairy Educator

Liz Gartman

Regional Crops Educator

University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension, Sheboygan County

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources; Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021 Aug 30. 5, Carbohydrates. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK600592/

- Q. Zebeli, J.R. Aschenbach, M. Tafaj, J. Boguhn, B.N. Ametaj, W. Drochner. Invited review: Role of physically effective fiber and estimation of dietary fiber adequacy in high-producing dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science, Volume 95, Issue 3, 2012. Pages 1041-1056. ISSN 0022-0302,

- Van Soest, Peter J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant. 2nd ed. Cornell University Press, 1994. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv5rf668.

- https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g3161

- https://extension.psu.edu/penn-state-particle-separator#section-1

Understanding Dry Matter: A Key to Better Dairy Feeding Management

Understanding Dry Matter: A Key to Better Dairy Feeding Management ▶️ Watch: Cows need fiber too! Storage and feeding tips to minimize nutrient losses

▶️ Watch: Cows need fiber too! Storage and feeding tips to minimize nutrient losses Troubleshooting Milk Fat Depression, Key Questions to Ask

Troubleshooting Milk Fat Depression, Key Questions to Ask Corn Silage Cutting Height Calculator – Background and Guide

Corn Silage Cutting Height Calculator – Background and Guide