Using Bovisync Reports to Assess Potential Impact of Heat Stress on a Dairy

How Can You Find the Tell-Tale Signs of Heat Stress in Your Records?

Milk Production

Fat Percent

Milk Quality

Reproduction

Clinical Mastitis and Transition Cow Health

Economic Impact

Take Home Messages

This article is part of the

How Can You Find the Tell-Tale Signs of Heat Stress in Your Records?

Here are a few of the key areas to watch for:

- Reduced milk production.

- Butterfat depression.

- Declines in reproductive performance.

- Increases in clinical and sub-clinical mastitis.

- Increased morbidity in transition cows.

In this fact sheet you will see examples of the resulting data you can use to unlock the power of your herd’s Bovisync records.

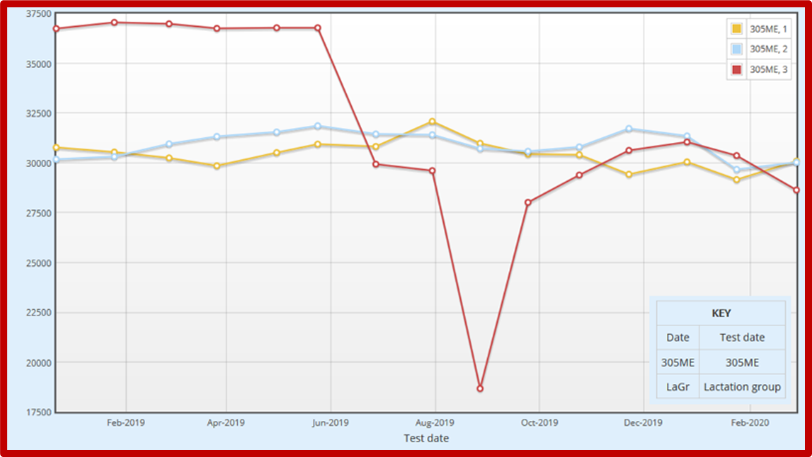

Milk Production

In Figure 1, 305 ME of lactation group 3 (lactation ≥3) started dropping in June until September. This is an example of what milk depression could look like when cows experience heat stress. 305 ME of first and second lactation cows remained consistent.

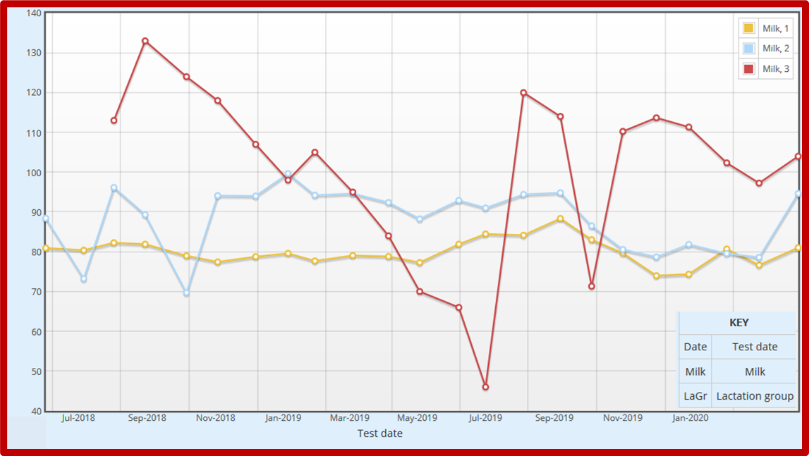

In Figure 2, a sharp depression in milk production in lactation group 3 is observed in July 2019. Compared to average daily milk production of February, milk production from March to July decreased about 30 pounds (range of 10 to 60 pounds) per cow per day.

There are no evident seasonal impacts on daily milk production in first and second lactation cows.

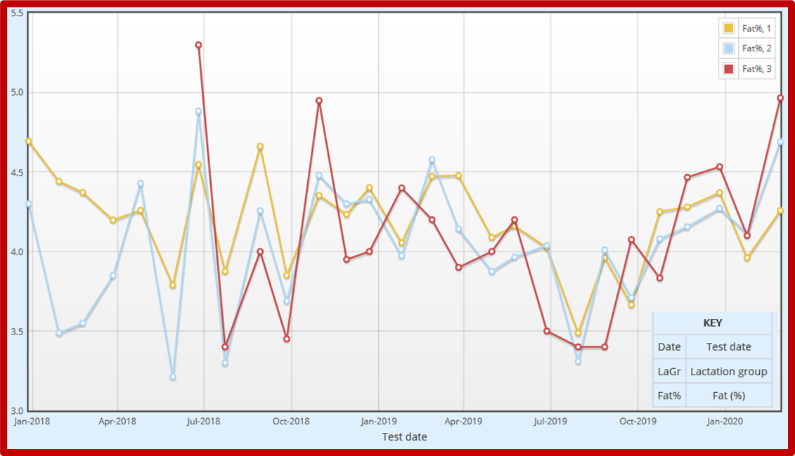

Fat Percent

In Figure 3, an arrow indicates a period where fat decreased in all lactation groups. Losses in all lactation groups were about 0.35 (range from 0.10-0.57) percentage points per month starting in June, continuing through September when compared to percent fat in May. Remember that milk fat varies depending on when (AM or PM) plant conduct monthly testing—fat is higher in the morning.

Milk Quality

In Figure 4, there is an increase of LSCC between July and October 2018. LSCC peaks in August 2018. Between July and August there a one-point decrease in LSCC.

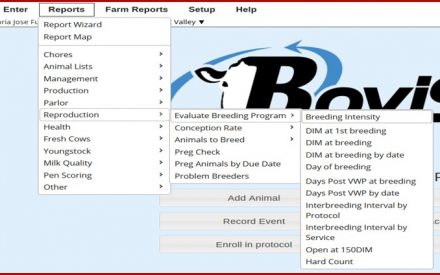

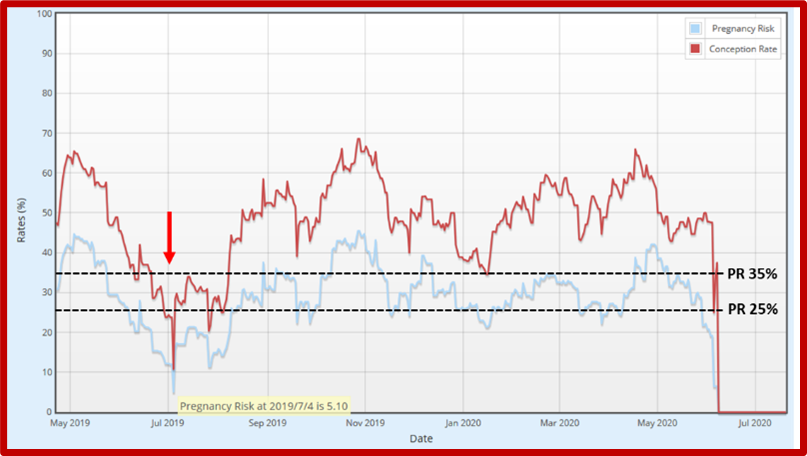

Reproduction

In Figure 5, pregnancy risk or pregnancy rate, which are used interchangeably throughout this factsheet, measures the percentage of eligible animals that become pregnant during a determined period of time. There is a sharp decrease in pregnancy risk and conception rate in July 2019.

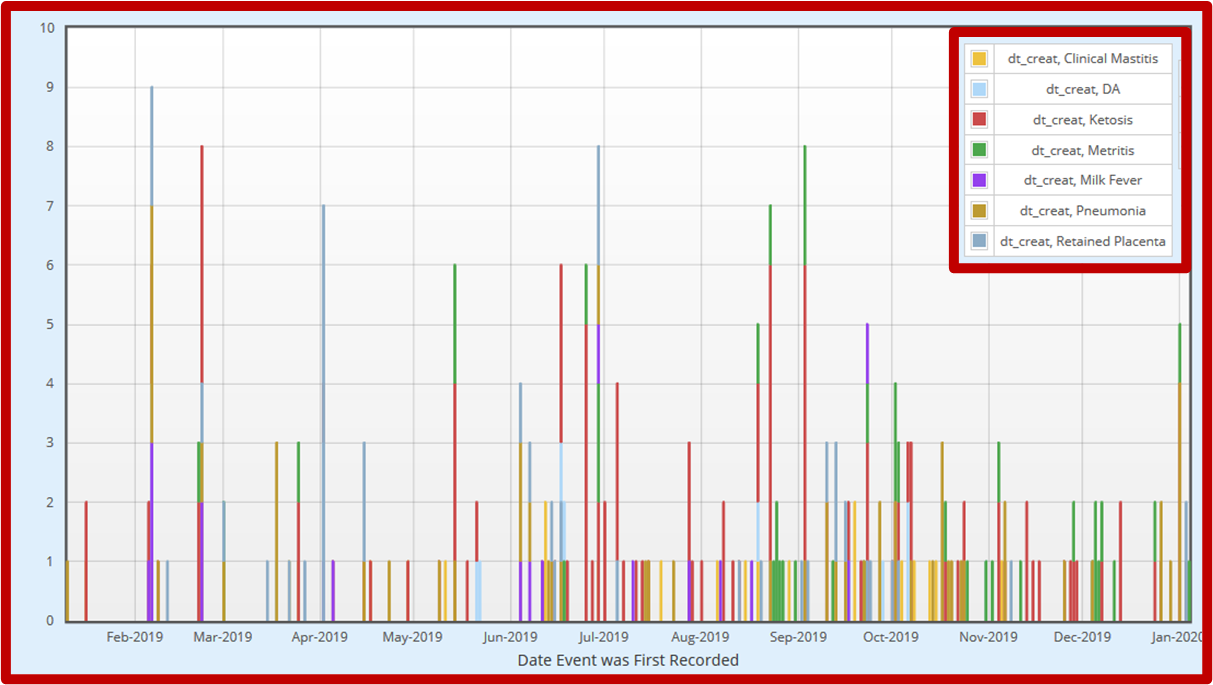

Clinical Mastitis and Transition Cow Health

Figure 6 provides a visual picture of health events during the critical transition cow period over the last year. There is an increase of health event during the summer months.

Economic Impact

Economic impact of heat stress is large. By following the information extracted from the Herd Summary, it is possible to estimate the potential losses.

Assuming a marginal milk production of 2.4 pounds per pound of feed, the loss would be $0.15 per pound of milk not produced (at $0.20 per pound milk and $0.12 per pound of feed). A daily loss of 30 pounds per cow per day (Figure 2) equals to losses of $4.5 per cow per day during some summer months.

Considering a price of $2.8 per pound of fat, 0.35% milk fat depression (Figure 3) represents a reduced price received for milk sales of $0.98/cwt due to heat stress during warmer months.

A decrease of pregnancy risk or rate from 35 to 25% (Figure 5) would represent a loss of $7.90 per cow in the month of July compared to the month of May (https://dairymgt.info/markov/reader.php ↗️).

Take Home Messages

- Use ME 305 to account for seasonal changes in milk production.

- Milk fat content can vary depending on the time of day the plant tests (morning vs. afternoon).

- Form a team to investigate seasonal depression in milk production. Involve your herd veterinarian, dairy consultants, nutritionists, and herd manager.

- Assess the economic impact of heat stress on your herd to motivate actions and investments in mitigating its effects.

Authors

Carolina Pinzón-Sánchez

Bilingual Dairy Outreach Specialist – As a statewide Dairy Outreach Specialist, Carolina identifies needs and incorporates research findings into high-quality outreach education programs around dairy production.

Victor Cabrera

Dairy Systems Management Extension Specialist, Professor, Honorary Associate/Fellow– Dr. Cabrera uses applied research, interdisciplinary approaches, and participatory methods to deliver practical, user-friendly, and scholarly decision support tools for dairy farm management aimed to improve dairy farm profitability, environmental stewardship, and long-term sustainability of the dairy farm industry.

Original Authors

Dr. Maria Jose Fuenzalida, Theodore Halbach, and Lyssa Seefeldt.

Original publication date: July, 2020

Revised: April, 2025